“..lend your ears to music, open your eyes to painting, and... stop thinking! Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to “walk about” into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do you want?”

The term synaesthesia refers to the neuropsychological trait in which the stimulation of one sense causes the automatic experience of another sense. It also is used to describe the deliberate connections between the various senses through artistic experimentation, most often linking the aural and the visual. Kandinsky might be modern art history’s most well known practitioner of such Visual Music, a term coined by Roger Fry in 1912 to describe his paintings, connecting the formal elements of the visual arts — color, line, shape — with the formal elements of music — tone, harmony, rhythm.

But the interweaving of sound and vision in art has been documented as far back as the ancient Greeks’ attempts to assign color to music. It has wended its way through western history, making notable stops in the 16th century, with Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s experiments in assigning color to the notes of the gravicembalo, and the 17th century, when Isaac Newton came up with his correlations between the color wheel and the musical scale, all preceding Kandinsky’s famous paintings in the early 20th century.

There is also a rich tradition of artist-musicians creating alternative visual musical notation, the most well-known probably being John Cage’s eclectic visual scores that are meant to be interpreted and played. It’s a history I have only just come to be acquainted with since our last opening at the Society for Domestic Museology back in November, featuring the work of artist Andrew Zarou, which was unlike anything we’d ever done before. The event was a celebration of synesthesia, artistic collaboration, and the generosity of spirit among artists talking openly about their work.

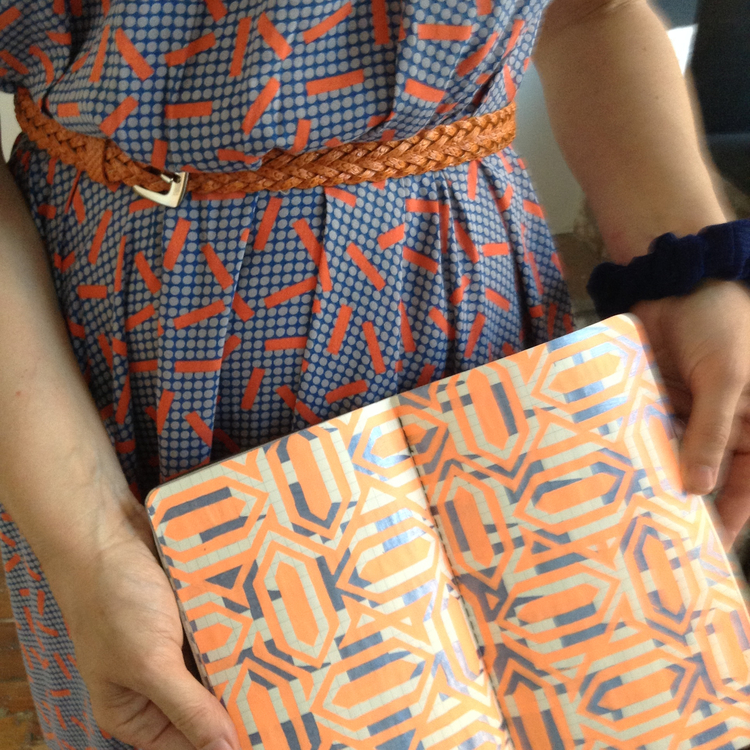

I first became acquainted with Andrew’s work when we were both attending the concert of a mutual friend. He showed me his notebook, a simple Moleskine of graph paper, filled with geometric drawings, defined by the underlying grid and a limited palette of gel pens. Despite these imposed limitations, the complexity and variation of the compositions were dizzying, with each page revealing a further iteration of the central theme.

Andrew is prolific, and the grid anchors his artistic practice in the series of drawings, which he refers to as an interplay between repetition and change. He titled the series Force Multiplier, referring to the grid as the factor that maximizes the effectiveness of this series, revealing the exponential variation that can be achieved through the limitations imposed by lines on paper.

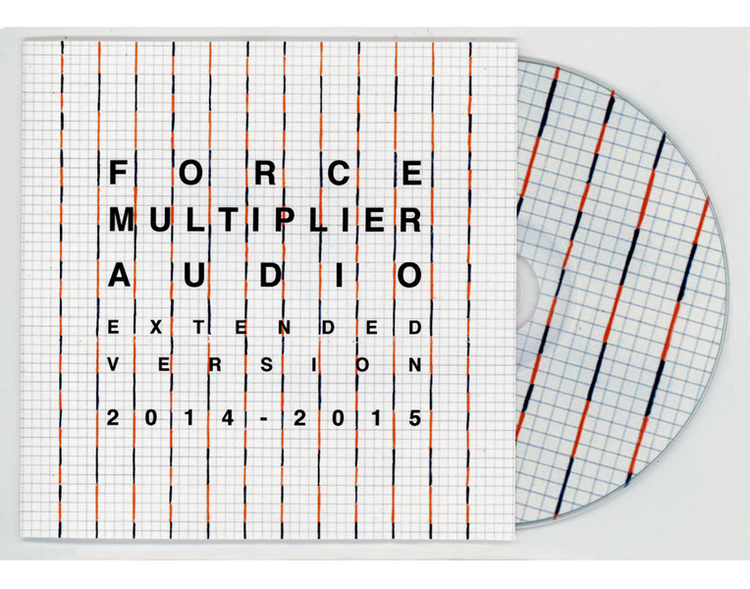

When I asked him to participate in SfDM, Andrew proposed presenting Force Multiplier Audio. For this project, Andrew selected a single image that had been conceived of as an alternative musical score. The drawing was then transformed into a limited edition silkscreen print by artist Kimberly Reinhardt. Andrew then reached out to his wide circle of sound artists and musician friends and asked them to compose sound pieces of two minutes or less, using the image as a starting point. It is a testament to Andrew's integrity and capacity for collaboration that thirty-three artists took up the challenge, resulting in 28 audio tracks.

I had attended the initial release party last summer at a small gallery in Brooklyn called Gridspace (a most appropriate venue for Andrew’s work!), where a few of the participating musicians had played their pieces live accompanied by a small exhibition of his sculpture work and works on paper. I was intrigued by the idea of extending this project and wondered how it would play out in a small domestic setting.

Andrew conceived of the evening as a kind of listening party inspired by Record Club, a regular gathering of friends and fellow music lovers for sharing esteemed pieces of music and sound. Founded in 1998 by artist and musician Dan Carlson, Record Club invites each participant to bring two audio tracks to share and discuss with the group. The gatherings begin with dinner followed by the first listening round, in which each participant plays the first of the two tracks two times — once without introduction or commentary; a second time with context and conversation among the group. After a break for dessert, the listening resumes with the second tracks.

Riffing off this model, Andrew suggested inviting the artists who had participated in the project to our apartment for a Force Multiplier listening party. Andrew would talk about the visual component of the work, Kim would discuss the silkscreen, and then each sound artist would play their recording and talk about their experience with the project. Thirteen of the 33 artists accepted our invitation, and we spent an invigorating evening listening to and discussing 10 of the tracks on the album.

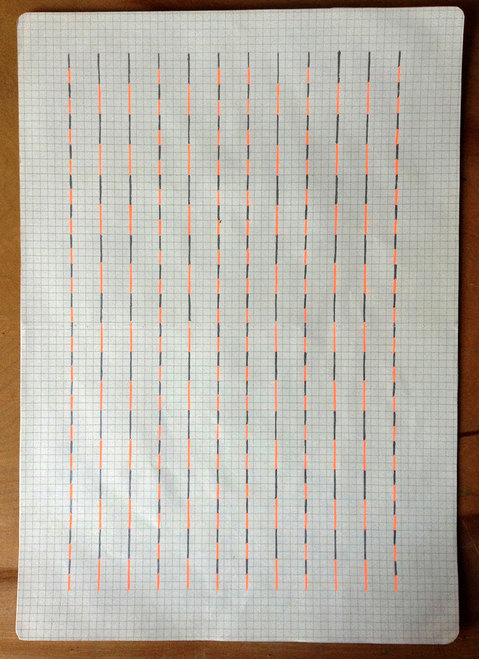

To get my head around the whole thing, I find it helpful to think of the Force Multiplier Audio project as a series of concentric circles. In the center, you have the original drawing by Andrew. The 41st in a series of grid-based compositions, it is an unassuming, yet deceptively complex drawing on a large sheet of graph paper comprising twelve vertical lines, each spaced four grid squares apart, that run in intervals of metallic silver and fluorescent orange. From a distance, they appear random, but looking closely a pattern begins to appear. There are two variations on the line: one with two-grid intervals and another with four-grid intervals. The lines themselves form a mirror image pattern on the page, a visual palindrome that takes some looking to discern. By the time I sorted that out, I had the distinct feeling that I was “reading” the piece, as if it was some kind of coded message to figure out. It made sense as a musical score, but offered no clues in how it should be interpreted.

The second concentric circle is the Force Multiplier screen print, which amplifies Andrew’s drawing with the silver and orange intervals appearing to hover above the grid, vibrating in some kind of otherworldly harmonic. Kim Reinhardt talked about the challenges of translating this work from drawing to print, the interplay between precision and imperfection. Kim and Andrew (who are a couple, as well as artistic collaborators) also talked about the personal dimension to this work. In the end, it’s the series of screenprints that become the work, with the original drawing acting as a blueprint.

The third circle is the sound layer of the project — another force multiplier that takes the basic concepts of limitation and repetition, and translates them into an analogous array of aural interpretations (say that five times fast). Among those present that evening, the musical collaborators approached the project in one of two ways: While some read the markings as a logical system and created layers of sound and rhythm that corresponded to numerological elements of the drawing, the others used the grid as a conceptual starting point, playing on notions of multiplicity, generosity, and endless permutations.

The SfDM opening itself provided the final fourth circle as we gathered in our living room, viewed the work on the west wall while listening closely to the 11 tracks, heard from each artist about how they approached the project, and shared our thoughts and reactions. While everyone had heard the compilation before, many of the artists had never met in person. Sticking with the conventions of Record Club, Andrew had each artist draw a playing card and follow in order from Ace to King. The following are a few of my notes on each of the tracks.

Photo by Jonas Gustavsson

First up was Colin Ocon (Track #14), who said he was inspired by the sonic repetition of the locked groove on a Moody Blues LP and layered sound, including a singing bowl, over a melodic rhythm that decayed with each repetition.

Ted Kersten (Track #22) took inspiration from his wife's sewing machine — both the sound of the motor, which provided a rhythmic anchor, and the notion of weaving patterns of sounds. Ted also raised the question of how Andrew’s pattern was meant to be “read,” horizontally or vertically. As a weaver, the print reminded me of the kind of patterns that weavers and knitters used and the link between Jacquard looms and early computing.

Brandon Koch (Track #28) used a recording his son at the playground to underpin his sung poem with acoustic guitar. The interplay between his song and the sound of son playing was a kind of dialogue, almost a secret language between the two. The child-like repetition of the phrase “one-plus-one” (“one plus one...is a mountain”) conveyed what Brandon described as “the generosity of the grid” and its infinite possibility. That lyrical riff became even more poignant when Brandon recounted that his son had gone through a liver transplant a short time before.

Kinsley + Langley + Ward (Track #27) took a literal approach to the drawing, using a singing bowl to translate the silver lines into bright accents over a meditative, impressionistic composition recorded live in a single take.

Dan Carlson (Track #21) noted that his track grew out of a process that was unlike his typical approach to composing and producing music. He began with a foundation of repetition, derived from "reading" the markings on the drawing, and built a more impressionistic interpretation upon that.

Steve Silverstein (Track #12) took a mathematical approach, dividing the 2 alotted minutes by 12 to get 10 second segments. Reading the print vertically, he translated the short intervals as fast segments and the longer ones as slow segments, to give the piece its structure.

Christina Clare (Track #11) also read the piece mathematically, focusing on the number 9 as a touchpoint. using two iPhones to layer keyboard tracks in a kind of digital-analog overdub process.

BNDL - Paul Benney, Charles Goldman and James Sheehan (Track 23) divided Andrew’s drawing into rows that each interpreted separately and then played together.

Instead of a mathematical or interpretive reading of the piece, Pen Pritchard (Track #20) went with a straight blues riff, played while "thinking about the mind of Andrew Zarou"

Leah Beeferman’s piece (Track #2) was a perfect finale — a kind of holistic interpretation of the whole piece that captured the way it seemed to vibrate and hum in a crescendo of sound.

To sit with these artists, listening to and talking about works that shared the same inspirational source, there was an almost harmonic, at times meditative, energy — all radiating from Andrew’s drawing.

The food was appropriately collaborative, spontaneous, and directly inspired by Andrew’s work. I had found a tablecloth that looked like a piece of graph paper and couldn’t resist the idea of creating our own version of his drawing using geometric-shaped foods in a similar color palate — cubed purple potatoes with yellow aioli, rainbow carrots cut into rectangles, polenta squares, cubes of bacon, and cheeses, all arranged on waxed paper over the graph lines. Our friend Clare Stollak Gustavsson, an amazingly talented caterer whose meticulously crafted pastries are as delicious as they are beautiful, followed suit with pumpkin pavlova with pumpkin seed and pecan brittle, composed of layers of spiced meringue with a pumpkin cream. There were also vegan/gluten free pumpkin donuts with a chocolate coconut frosting and candied ginger. It was November, after all.

We started the Society for Domestic Museology to celebrate and build communal experiences around the creativity of our friends. And we’ve been so gratified by the thought, respect, and humor people have brought to those conversations. Andrew Zarou and the collaboration he built around Force Multiplier Audio took that to a mind-blowing new level. In the few months since the opening, I find myself listening to the audio compilation closely and often, and continually finding my own new repetitions and permutations on his generous grid.

We started the Society for Domestic Museology to celebrate and build communal experiences around the creativity of our friends. And we’ve been so gratified by the thought, respect, and humor people have brought to those conversations. Andrew Zarou and the collaboration he built around Force Multiplier Audio took that to a mind-blowing new level. In the few months since the opening, I find myself listening to the audio compilation closely and often, and continually finding my own new repetitions and permutations on his generous grid.